Kitty Genovese: Who She Was and What Really Happened

The murder of Kitty Genovese, a 28-year-old bar manager in Kew Gardens, Queens, New York, is a significant murder in NYC history. Kitty was murdered in 1964 in broad daylight in the street outside her apartment. About a week later, on March 27, 1964, after a police officer mentioned the case to a New York Times editor, the New York Times ran an article headlined “37 Who Saw Murder Didn’t Call Police”. The editor alleged 38 people saw her being stabbed repeatedly in the street outside her apartment block and did nothing.

It said: “For more than half an hour, thirty-eight respectable, law-abiding citizens in Queens watched a killer stalk and stab a woman in three separate attacks in Kew Gardens.

That was not true; according to witnesses and police officers who were there at the time, only two neighbors witnessed the crime from their windows. The rest came out into the street after hearing screams.

Although the article turned out to be factually incorrect, the thought of someone being publicly murdered while 38 people did nothing is terrifying and rightfully sat in the back of public consciousness for decades.

It brought a negative reputation to urban culture and especially NYC culture while on the eve of a political and cultural revolution. There’s no doubt the Genovese murders further shaped the way NYC viewed and handled crime. It also became a highly covered topic in American psychology for decades as a phenomenon psychologists coined “the bystander effect”.

Who Was Kitty Genovese?

Catherine Susan “Kitty” Genovese was born on July 7, 1935, to Vincent and Rachel Genovese in Park Slope, Brooklyn, New York, where she was raised most of her life. Genovese was the oldest of five children and a graduate of Prospect Heights High School.

A mugshot of Kitty Genovese during her 1961 conviction for illegally collecting horseracing bets from bar customers.

Ironically, her mother had witnessed a murder that ushered her parents to move to New Caanan, Connecticut in 1954. However, she stayed in Brooklyn with her grandparents as she was engaged to be wed. The marriage was eventually annulled when Genovese came out as a lesbian.

Genovese lived in Brooklyn for ten years after her parents moved to Connecticut, likely staying due to NYC’s LGBT community, which was known to be stronger than CT’s, even though LBGT history was in its infancy.

She worked various secretarial jobs in New York City during the day and as a bartender for a local bar at nighttime. She lost her job when she was arrested and fined for taking horseracing bets from customers at the bar. She quit her clerical career to focus on her food and hospitality career full-time. She worked for Ev’s Eleventh Hour, a sports bar in Queens, as the bar’s acting manager. She would work double shifts to save money in hopes of pursuing her dreams to open an Italian restaurant.

She was living with her girlfriend, Mary Ann Zielonko, whom she had met at a Greenwich Village gay bar a year prior to her death. The two lived in a relatively safe area in Queens’ Kew Gardens in a rented second-floor apartment. The neighborhood had a positive reputation for being peaceful and quiet.

What Really Happened to Kitty Genovese?

On March 13, 1964, at about 2:30 a.m, Genovese headed home from Ev’s Eleventh Hour in her iconic red Fiat when she was discovered by a man who was sitting in his parked Chevrolet Corvair. The man spotted her while she was waiting at a traffic light to change on Hoover Avenue. She arrived home at 3:15 AM and parked her car at the Kew Gardens Long Island Rail Road train station roughly 100 feet away from her apartment’s door. He parked his car on the other corner of the block near the bus stop and exited his car with a hunting knife.

Genovese saw him approaching with a hunting knife and ran towards the back entrance of her apartment building, where the man overtook her and stabbed her twice. Stabbed in the back, she screamed for help, which prompted her neighbor Robert Mozer to shout “Leave that girl alone!” at Moseley from his window. Startled, the perpetrator ran back to his car and drove away.

Kitty somehow staggered her way, barely conscious, to the back alleyway of her building. She was no longer in view of her witnesses and tragically her serious wounds and fading consciousness made it impossible for her to cry out for help or make her way into the locked building.

Neighbors watched the perpetrator return in his car ten minutes later. Moseley, who was unrecognizable due to a wide brimmed hat shadowing his face in the darkness, searched the parking lot, train station, and perimeter of the building until he discovered her near the back door–out of view from the witnesses.

He then stabbed her again multiple times with the hunting knife, raped her, stole her cash, and ran away. The attacks were estimated to have taken about thirty minutes total and Kitty’s wounds implied that she had put up her hands in attempt to defend herself.

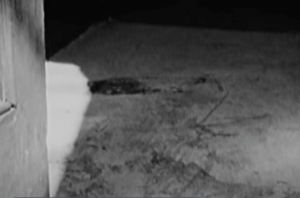

The spot where Kitty was discovered. She was comforted by her neighbor, Sophia Farrar, while they waited for the ambulance to arrive. (Photo: The Witness)

Kitty’s neighbor Sophia Farrar went looking for her and finally discovered her fatally wounded in the alley near the backdoor. Sophia yelled for somebody else to contact the police, which unknowing to her had already been called twice. The issue was that the attacks had occurred prior to the implementation of 911, which meant that the calls had to be fielded to the local precinct, and as result were not assigned proper priority.

Another witness had called his friend to ask for advice on what to do, and another had called the police reporting that a woman had been stabbed and was staggering around.

Kitty Genovese did not die alone. Upon Sophia’s discovery, she did not leave her side. Sophia held her and whispered to her “help is on the way” until an ambulance came. Unfortunately, Genovese passed away due to fatal injuries compromising her lungs on the way to the hospital.

Potential Suspects in the Investigation

There was an early stigma about lesbian couples being prone to jealousy more than other heterosexual couples that the police purported and projected onto her girlfriend, Mary. Therefore, as early as 7 a.m, Detective Mitchell Sang questioned Zielonko in the apartment she shared with her deceased girlfriend. Zielonko was aggressively questioned by Detective John Carrol and Jerry Burns for six hours straight.

During the questioning of Zielonko, Detective Mitchell Sang encountered neighbor Karl Ross, who was offering her liquor to console her. Sang found Ross offensive and arrested him for disorderly conduct. In addition, Sang was aware Genovese’s body was found at the bottom of the stairs leading to Ross’ apartment. Ross was also treated as a suspect.

Just about six days later, a man by the name of Winston Moseley had been arrested for robbery in Ozone Park when a stolen television was discovered in the trunk of his car. Raoul Clearly became suspicious of the robbery when he saw Moseley removing the television from his neighbor’s home. He claimed that he was helping the neighbor move, however another neighbor, Jack Brown stated they were not moving. Clearly immediately called the police and Brown cut a line on his car to prevent Moseley from leaving prior to the police arriving.

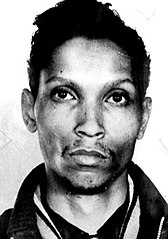

Who was Winston Moseley?

Winston Moseley was a working 29 year old African American at the time of his arrest. On the surface, Moseley appeared to be an innocent and hard working man. Married with three kids and no previous criminal record, Moseley was a full time employee for Remington Rand, where he worked as a punch card machine operator.

A mugshot of Winston Moseley during his arrest.

When Moseley was arrested, his car was considered as potentially being the one that had been reported to the police by her neighbors. It didn’t take too long or too much questioning – They noticed scabs on Moseley’s hands and Moseley eventually admitted to murdering her and two other women while in custody. One of his confessed slayings, 15 year old Barbara Kralik, brought some confusion as another suspect, Alvin Mitchell, had admitted to murdering her already. He also admitted to raping them and committing around 20 to 40 burglaries. Due to the suspect’s confessions, Moseley was only convicted for the murder of Kitty.

Despite Mosley confessing his crime and reciting his actions in vivid detail, he still made a plea about his insanity. Ultimately, he was convicted of murder in the highest degree and given a death sentence which later changed to life imprisonment in 1967. He was denied parole eighteen times. At 81 years old, Winston Moseley died in prison in 2016.

It’s never been known if there were any specific reasons why he choose Kitty that night.

How the Media Failed to Properly Report The Story

Two weeks after the incident, an editor of the New York Times, Abe Rosenthal, reported that supposedly 38 people had seen Kitty being attacked and even heard her screams, but none called the police or offered any other assistance. The details were later found to be false; actually some of the witnesses that had been allegedly “inactive” had actually been asleep, and others were not close enough to see or hear what happened.

Competing WNBC police reporter Danny Meehan did notice inconsistencies within the story and made claims that were false, however they were unwilling to persistently challenge the editor at the time, who was considered an influential figure in the editorial industry.

“It would have ruined the story.” -Martin Gansberg, New York Times reporter

It wasn’t until the 2000s–after Rosenthal had passed away–that the story was openly questioned. The New York Times eventually apprehended the article in 2016 following the 2015 documentary featuring Kitty’s brother William, The Witness, that discussed the media mishandling and misinformation. In the documentary, William emphasized the ramifications the article had on his family by stating that his mother, whom had moved to CT after witnessing a murder in Brooklyn, passed away due to a stroke the year following the media coverage, and that she had passed not knowing the true events of what had happened.

The thought of so many law-abiding citizens witnessing a brutal murder whilst remaining inactive disturbed even the general public. Understandably so, it remained in the back of the public’s consciousness for a long time and caused an emphasis on urban perception and protocol.

Legacy & Impact

The case of Kitty Genovese is often cited as an example of urban apathy. Many New Yorkers at the time believed that the story was accurate – which reinforced a stigma of “urban apathy”. Indeed, the shocking headline echoed throughout the world and reinforced a critical view of New York society and urban city culture on the whole.

“See Something, Say Something” sign written on the stairs near a NYC subway. NYC launched the “See Something, Say Something” campaign after the 9/11 terriorist attacks. Since its launch in 2002, NYPD has investigated 42,000 tips.

Despite the lack of evidence for most of the claims made in the original news stories, the case prompted many changes in law enforcement and emergency response practices. The murder has been cited extensively as a contributing factor in the passage of 911 in 1968, which led to the creation of emergency telephone number systems nationwide.

Genovese’s murder has also been cited as a landmark event in American psychology because of the bystander effect phenomenon it inspired. The term is used to describe situations in which individuals are less likely to offer help or intervene when other people are present.

The case sparked debate about the causes of this behavior and its implications for human nature: Are we inherently apathetic? Or do we become so out of fear of intervening in situations that are none of our business? Modern psychology today believes that the spectrum of emotions during these situations are much more complex. When bystanders are involved in these type of situations, it’s generally thought to be as a result of strong emotions such as their fear, apprehension, and uncertainty.

Did the Genovese Murder Inspire Future Crimes?

After the Genovese murders, murder and violent crime steadily began to rise until it peaked at an all time high during the Crack Epidemic of the 1990s. In fact, the worst decades of NYC in terms of crime were thought to begin throughout the 60s to 90s. Part of this odes to the fact the United States was on the eve of a radical political and cultural revolution, with the Vietnam War and all the cultural movements at the time coming to a head.

However, what if the widespread notion that most urban crimes involve bystanders contribute to overall crime? After all, a criminal could be more likely to commit a murder under the impression that they’re able to get away without being reported for it. If this is the case, perhaps it contributed to later crimes such as the Central Park Jogger attacks in 1989.

Takeaways from the Genovese murder

The man who first heard Kitty said he didn’t want to get involved, and he went back inside his apartment.

“I thought someone would help her,” he says today. “I didn’t realize how bad it was until I saw the movie.”

While we like to think this is a tale about apathy, it’s actually about the opposite. It’s a story of how we are hard-wired to help each other — and how sometimes we don’t.

Genovese’s murder is often used as a cautionary tale about the dangers of urban life in America. But it can also be a reminder that most of us want to help when we see someone in trouble, even if it means putting ourselves at risk.

The case also highlighted the negative impact of media coverage on public perceptions and attitudes towards victims. The fact that most of those who witnessed Genovese’s ordeal were older than her and had never previously met her may have caused them to distance themselves from her plight, assuming she was somehow responsible for her death because of her lifestyle choices.

—

Hungering for more true crime? Take a look at the famous murders that changed America.